Most Recent News

Popular News

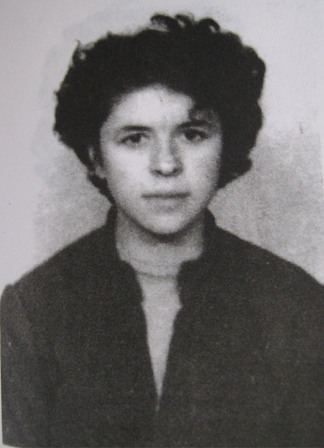

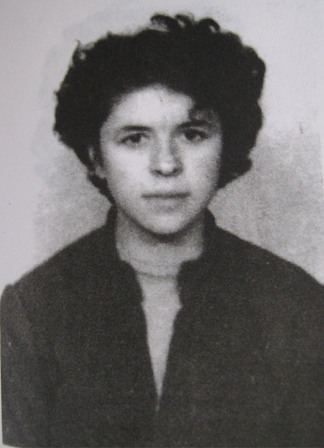

The Story of Stela Covaci. Stela was a victim of communism under the Communist Party of Romania in the 1950s.

It’s 1956 Bucharest, Romania. The Communist Party of Romania (arrogant twats mostly used as USSR lapdogs) holds complete control of the country. Stela Covaci was young back then. She was enrolled in the University of Bucharest, a flagship university in the capital of Romania.

But before we get to the events that transpired at that university, we need to take a step back to the early 1950s Romania. To see the life she, and every other Romania, lived.

Bucharest is the capital of Romania. The communist party haven taken control on April 13, 1948, called the shots.

This new government instituted a new constitution, which was practically a clone copy of the Soviets 1936 constitution.

It sought to ban anything it found “anti-democratic” or “fascist” in nature. This ended up being interpreted as anything that went against the communist propaganda.

Very few non-party or Securitate officials owned homes. Most citizens lived in an apartment.

This apartment was not purchased by Stela or her family. It was assigned.

And it was assigned based on family size.

Stela Covaci considered herself very lucky in her family’s apartment, and many considered her ‘royalty’.

Why?

Because she didn’t have to share it with another family.

You see, most of the housing available in Romania ended up being distributed into “living blocks”. As in, a family of one may need 400 sq ft. Whereas a family of two needs 600 sq foot. So what if the apartment had 1000 sq foot? The two families would be combined and forced to live together.

Stela Covaci was lucky in that sense. More-so than other Romanians who had to share their homes with up to 5 different families of strangers, because of the communist “To each according to their needs” philosophy.

While not ideal, it allowed her the ability to grow up. And in truth, most of the younger generation didn’t know any better at the time. They thought life had always been like this, and always would be.

The meals generally comprised (rationed) plain vegetables and unappealing manufactured goods.

Meat was incredibly rare. Stela’s mother had to wait in huge queues to acquire enough for one meal. The only other way was if you knew someone at the grocery to sneak some under the table.

But it was also dangerous because if anyone was caught with more than 1 kilo of meat, you’d immediately be arrested. The meat would be confiscated, and it’s likely the offender would face large fines or imprisonment.

But that didn’t matter to Covaci much. The meat was packed full of crappy soy (to increase availability) anyway. Making it into a kind of 60% meat, 40% soy mush that did little for anyone’s taste.

Fresh fruit was also rare. It made a great treat to receive an orange or a banana. But it could only be expected maybe once a month, at certain times of the year.

Even those with money seen no end to this. Covaci’s family was relatively wealthy, but still could not acquire these goods.

Because even with a lot of money, the currency was devaluing fast. A loaf of bread was $50 one month, $100 the next. So the money everyone earned proved no cure to any of these ailments.

Along with that currency problem, everything was rationed by the communists. No one could buy more meat than the party allowed. Unless it was on the black market, which would then make it a significant risk, as you could be gambling with your life in one of the communist prisons.

Luckily, every once in a while Stela and her family could get ahold of some fish and albinuta. It would require her father to stand in line for almost a day, but he would do it with a smile for her.

Her family was of great support. Even when she was younger, she remembered her parents going to the back of restaurants and bribing the cooks to give them an egg, risking the wrath of Securitate just so Stela wouldn’t go malnourished.

Stela and other Bucharest residents would receive warm water for a few hours in the morning and the evening.

The communists made sure to ration the heating of water to reduce overall costs. Which made sense to most residents, because who really needs warm water all day?

Usually, the day was centered around these time periods. As you needed warm water to bathe or cook certain food, all other activities had to be put aside to make sure you did not miss the window of warm water availability.

Heating was available during the colder times. But hardly anyone in Bucharest trusted it.

Most residents survived strictly on extra clothing and homemade heating sources.

It became a simple fact of life that you could never trust that heater to work when you needed it most. It would almost always fail, or be shutdown, at a critical time. So they had to improvise.

Many residents, Stela included, had specific outfits to survive the heating outages. It usually included a large assortment of bundled clothing and blankets to wait out the days until the heat returned at half-capacity.

Electricity also had plenty of problems. Whether it was an issue with the power-grid, or the communists shutting it off to save energy, no one ever really found an answer.

What they did know is that roaring power outages were commonplace. It wasn’t unusual for it to happen multiple times a week, for hours at a time.

Because of the lack of power, the communists also cut all electricity after 9PM. Making the residents wait until the power workers made their rounds in the morning to turn it on again.

Television was also restricted to about an hour a day. Ironically, the power outages never occurred during the broadcasting times.

The Covaci family didn’t watch it much. There were only 2 stations, and both stations were nationalized. They only ran communist-inspiring shows daily.

With the option of watching TV for one hour between one communist show on Channel 3 and one communist show on Channel 4, well let’s just say it didn’t leave many options for interesting entertainment.

During her growing years, Stela Covaci noticed the constant in-fighting in the education realm.

The administrators and teachers would fight endlessly over lessons, and as students grew older, they too became combative.

One of the finest points of discrepancies in the education system was with the Russian language.

It was taught to all students in Bucharest, along with communist politics. Many students felt like they had lost their country to Russia and felt disgusted by the fact they had to learn their language.

Between that and the teaching of communist propaganda, it created an incredibly hostile environment. But Stela knew better than to speak up, as the communists made it very clear that any form of disobedience would be met with swiftly and harshly.

That’s how she lost a close friend, Maria Vasile. When Stela was in grade 12 (American equivalent), Maria had the bravery to ask why she must learn of their invaders’ language. She was escorted out of the classroom later that day, and Stela never heard from her again.

The most common methods of getting around Bucharest were walking or taking the bus/trolley.

There were very few cars, and it was incredibly hard to acquire one for yourself.

The process usually involved signing up to be put on a wait list. After you had signed up, expect about a 10-15 year wait until the car was given to you.

Of course, you could speed up this process with very high bribes to Securitate officials. But why even bother with a car? You wouldn’t be able to drive it much, anyway.

Because even after you had received a car, you then had to play the license game.

What was the license game? Well, it was your given days to drive. If your license ended with an even number, you could drive Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday. If it ended with an odd number, you could drive Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday.

The communists said this was because of bad traffic congestion. They lied. Everyone knew it was because it was a way to conserve gas. They had to ration it severely, or it would continue to run out, much like the electrical power grid.

And even then the rationing wasn’t done. If it even so much as snowed an inch in November, all car traffic was stopped until next Spring. The snow could clear up the next day in Bucharest, but you wouldn’t see one car on the street.

So what ended up occurring was that most car owners were Securitate. This was because they received free gas and a quick wait period. You could always tell when they drove by, as they seemed to not have a care in the world, as Stela trudged through terrible rain, fog, and hail.

So, Stela Covaci and her family stuck to the bus. It wasn’t pleasant, as it was always shoulder-to-shoulder, but it beat the car restrictions.

With all of these problems, Stela was still content. Why? Because she didn’t know any better. She didn’t know how much better it was in other places. The bit of information and black market knowledge she received through the grapevine was disgruntled and non-assuring.

And with the TV constantly saying how great things were, it made it seem as though Bucharest was the best city in Europe.

The communists always said that Bucharest had the best living standards in all of Romania.

But if those were the best living conditions in the entire country, I shudder to think of what those Romanians living outside her walls must endure.

Ms. Covaci was accepted into university and began her studies in 1955. She did not know, but she went to university under a Stalinist educational policy that the Stalinist government enacted.

But what was Stalinism?

Most didn’t really know. They only tended to hear about it through Radio Free Europe. Which was a Western powers radio that broadcasted information and news into communist-controlled territory.

The average Romanian tended to be quite skeptical of those radio broadcasts. They saw the United States and Western powers as lackluster and passive toward their own plight.

The universities were not so. Many students, and even faculty, listened to them quite frequently.

Through the news from numerous outlets, including Radio Free Europe, the students were able to hear about what was happening in Hungary and Poland.

In 1956, Hungary and Poland, popular uprisings began to become the norm.

Because of the Soviets atheist attitudes, many citizens felt as though the Russians were trying to eradicate their own faith. You see, under Soviet control, religious bodies were largely banned.

They were restricted to their own places of worship, and any public demonstrations (even so much as a necklace) would result in imprisonment.

Even then, the churches weren’t safe. Soviets would regularly invade them under false premises just to shut them down and imprison the church workers.

Students, activists, liberty-seekers, and even the average citizens amassed to resist the Soviet states’ laws and harsh treatments.

This defiance spread to Romania, where students and workers began to demonstrate at university and small set-up shops in Bucharest calling for better living conditions and an end to Soviet control.

The Hungarian uprising provided a lot of inspiration to the Romanians. They thought if they fight, why can’t we?

Stela Covaci agreed with this mindset. She later agreed to join the ranks of the protests.

Sadly, the Hungarian story does not end well. As at the end of 1956 (November), Moscow mounted a bloody invasion of Hungary and slaughtered tens of thousands.

But what happened in Romania? How did they fight back?

Stela and the other students/faculty decided to follow in Hungarian footsteps and seek better living conditions for themselves in early 1956.

They demonstrated peacefully in Bucharest and attracted quite a lot of publicity.

From signs to covert discussion, they did everything they could to get the message across. A mission to bring a brief amount of unity with their Polish and Hungarian brothers & sisters that were also under the same authoritative nightmare.

The students went so far as to send a letter with many questions to a man named Iosif Chisinevschi, who was the vice president of the Council of Ministers.

The questions were not ideological, because they knew that would immediately draw in the tanks. Instead, they asked questions such as:

As you can tell, these questions were superficial. They did not care so much about the “fence post” and “wood production,” as they did about peasants having to make an over-abundant amount of coffins for dead children dying from malnutrition.

The questions were worded solely to open a dialogue, not directly attack the underlying ideology. Even though that’s exactly what Stela and her classmates desired to do.

Sadly, but unsurprisingly, they never received a response.

As mentioned before, the Soviet Army invaded Hungary and instituted a brutal repression of all speech at the onset of November, 1956.

Stela and the organizers within Bucharest, Romania realized that they had practically no chance of success.

And yet, they kept on. They believed that the movement had to continue, and the protests had to take place. If not for them, for the Hungarians.

Because of this, sweeping new powers came to the police and military forces in Bucharest. The command was given enormous powers, with the right to order troops to open fire and declare martial law in any part of the country.

The command was also immediately given the “right” to suspend classes in institutions of higher learning.

On the night of November 4th, they used this power.

Troops from the Ministry of the Interior invaded University Square at Budapest University.

Traffic was halted and searched, and the entire area once filled with students with backpacks was now filled with black-masked soldiers with automatic weapons.

The protest planned for that day became impossible to finalize. Troops swarmed the buildings and watched the students as they left.

All the students that had planned to protest, including Stela, walked away as soon as they saw what was happening. They knew that any word would have them immediately handcuffed and blindfolded.

As Stela walked by the entrances to the square, there were party members standing around.

They were gathering names for who all was in that area. They were looking for those who were going to protest. Stela, sadly, had given her name. She had no other option.

At the same time, the Communist Party of Romania set up strict surveillance of the university and nearby “hotspots”. Actions were taken against faculty and students by university administrators, as those admins feared for their own safety.

Students who were “suspected” (It was no secret) of being involved were expelled. Faculty fired. And covert police were put in place to monitor the remaining behavior.

Even the student organizations became co-opted. The police ‘convinced’ the top organizers to immediately identify and request expulsion for those with the smallest inkling of being a protestor.

The university would immediately grant any expulsion request. Many individuals who weren’t even involved with the protest were expelled.

Stela scrapped by… At first.

Walking at the university, Stela was overrun by security forces and arrested.

The charge?

A crime of conspiracy against social order.

Whatever the hell that means.

Stela felt immense fear being loaded into the black, unmarked van (A trait many communist parties used). Fear from the hundreds of thousands who had died while imprisoned in Romania. While the “official” judicial execution number was low, that was only because they didn’t count those who died awaiting trial or during their sentence.

While Stela was imprisoned, she heard rumors and whispers from the guards and the outside world.

She learned that Nikita Khrushchev (Soviet leader) saying that there were:

Unhealthy moods among students in one of the educational establishments in Romania.

And further stating:

I would also like to congratulate the Romanian Communist Party on having dealt with these protests… quickly, and effectively.

This sent Stela into a rage. All they sought to do was voice grievances with the poor living conditions. Why was her mood less ‘healthy’ than the communists? Surely, her living conditions were unhealthy, as was her “mood”.

When she finally received her sentence, she learned she would be spending years in prison. After prison? Well, then she would be under strict surveillance for the next 20 years.

And she learned she would never be allowed to return to finish her studies.

Years after her release and subsequent monitoring, Stela married to Aurel Covaci.

The communists in Romania never ceased their harassment toward her. In between the police visits and fines, it reached a boiling point in 1987.

In 1987, the Covaci family had a home-demolish order put on their family home. The communists decided it would be better suited as a newly remodeled bakery shop.

While she put up a fight, and even organized more protests over it in her neighborhood, those efforts failed. And she was forced back into an apartment, with her family’s home being destroyed.

Under the threat of imprisonment until death, Stela backed down. For herself and her family.

The communists stopped at nothing to continually silence her and berate her into submission. And largely, it worked. It becomes impossible to fight against an entire government and their pawns when everyone else has already given up.

While I titled this article “The Tale of Stela Covaci”, it is not a fictitious tale. This is a real person, who lived her life under the very real threat of communism.

She was a true victim of communism.

And this is just one story out of hundreds of thousands in Romania, and hundreds of millions worldwide.

A Romanian obituary I found through digging online had a final sentence about Stela that said:

Dumnezeu să te odihnească, Stela Covaci, și iartă-ne!

I’m not fluent in Romanian, but what I could gather it says:

God Rest You, Stela Covaci, and Forgive Us!

I hope God will rest her, and I likewise hope that those of us who live on will continue to remember her story, lest we repeat it.

Comments are closed.

(Learn More About The Dominion Newsletter Here)

My parents grew up in Romania at that time. Everything in this article seems like they are experience minus the automobile, almost swore my parents had a automobile, dont think it took that long for them get one. But am not sure.

Anyway, thanks for sharing our story. Seen it on a Romanian forum. God bless Stela and her sacrifice!

Glad you enjoyed it, thank you.

My grandparents had one too but it was because they had some connection to the local gov. Maybe yours did? I dont know, i was real little when they moved to France.

Communism has failed or became a dictatorship everywhere it was tried, i’ll never understand why people still think it is a good idea