Most Recent News

Popular News

Chapter 3: The Cycle of Collapse for “Enclavism: A New Government Designed to Conquer the Political Cycle of Collapse” By Kaisar

Previous Piece: The Enclavism Book: Chapter 2 – “The Legacy Options by Power Source”

As we demonstrated in the last chapter, all government frameworks have some positive and negative elements. This is why most of us can relate to the proponents of nearly any form. Given personal desires and the current conditions of a nation, certain political leanings can make perfect sense. It’s also why we witness political leanings evolving over time, given the changing internal conditions of any nation. A late-stage republic will create a lot more radicals than the early stage alternative.

Yet, we’ve also seen that none of these frameworks are sustainable in their current form. They all have certain negative attributes that lead to their degeneration and decline. No legacy system has the possibility of surviving the political cycle of change. None were considered sustainable. They will all collapse given enough time.

Which brings us to the point of Enclavism. Which is breaking this political cycle of collapse. Or, as the ancient Greeks called it, anacyclosis.

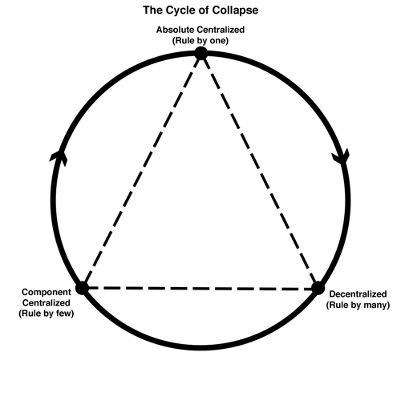

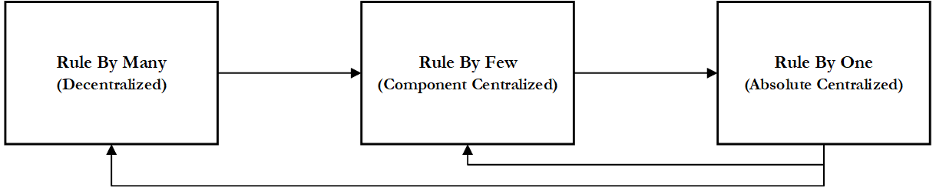

Understanding the cycle is simple. Over time, the governmental framework decays. It then changes or collapses into a different framework regime. Then, eventually, that new regime also degrades. We constantly loop in and out of these government cycles, experiencing continual rebirth and subsequent death.

Let’s discuss a specific example. We begin with a representative style of government. Our representative system of government degrades, resulting in a socialistic system with an oligarchical ruling class. This is a rule-by-many degrading into a rule-by-few. Eventually, financial strife causes problems in our oligarchy leading toward an ideologue who threatens the ruling few. He wins through mob violence. Thus, we trade a rule-by-few into a rule-by-one. This rule-by-one form inevitably degenerates because our ruler’s children are not as benevolent as the first ideologue, so the people overthrow him. Our rule-by-one vanishes and a rule-by-many returns. Then the cycle continues indefinitely. This cycle of political regime change has been repeated since time began. Nothing has been able to stop it.

Sometimes the changes and decline are rapid. Sometimes certain forms are able to hold on for longer than others. But the result is always the same. We are constantly trapped in this cycle of continually changing regimes.

Plato spoke of this with his theory of Five Regimes and Kyklos.[i] Classical Greek author Polybius provides arguably our most helpful analysis that becomes the bedrock of future study. He called it anacyclosis.[ii] Aristotle also wrote extensively on this subject.[iii] Renaissance authors such as Machiavelli spoke of the political shifts of anacyclosis.[iv] Plenty of others, such as Sir John Glubb and authors of the Enlightenment, have documented their experience with this effect.[v]

To develop a modernized version, we must first fully understand their findings. We will focus most of our time on Polybius: he created the most fleshed out version that most modern authors expanded upon. Firstly, however, we will mention Plato’s theory.

We start with Plato and his Kyklos theory. Plato noticed five regimes that contribute to the cycle. These are aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny. They degrade in that order. Aristocracy is where a small ruling caste led by a philosopher king grounds the country in wisdom and reason. This type of government eventually became untenable due to miscalculations over time by the absolute rulers. Timocracy is a representative style government where inferior individuals are allowed involvement in governance. It is the inevitable future of aristocracy. Plato believed this political government was what caused the eventual degradation of culture and constitution. With that degradation comes opportunists looking to gain at the expense of the nation. So naturally, following timocracy, we have oligarchy, which we previously discussed in-depth. This form of oligarchy led to further centralization and corrupt leadership due to the inferior, greedy leaders. After oligarchy, Plato believed in the switch to democracy but a specific form of it. Plato spoke of democracy in terms of the man who does not resist lustful ventures, such as a lifelong purpose geared toward gaining wealth. He also believed democracy would quickly become slavery through mob rule. So, oligarchy would fall into an even worse form: slavery through debauchery-laden mob rule. Given enough time, the mob oligarchs’ power would dwindle and thus their hold over the population. Plato then mentioned this degenerative decline would result in tyranny, as people desired discipline and order at any cost to escape mob rule. To get this order within the state, tyranny would be necessary to suppress the mob. The problem was that the tyranny would not end with the mob. Over enough time, the tyrant would be overthrown by his people because of his harmful actions. From tyranny, we return to aristocracy as the tyrant falls and noble aristocrats seize control.

We hope the last paragraph sounded familiar. While we disagree with Plato on some key areas, the general concept of political decline and their reasons are similar. The pathway and problems are much the same now as they were during his time.

Let’s take it one step further and consider Polybius’s anacyclosis, which expanded on Plato’s Kyklos.

Polybius created the most developed version of anacyclosis, which is still very relevant to modern times. He states that the government forms cycle through in the following order: (1) monarchy (2) tyranny (3) aristocracy (4) oligarchy (5) democracy, and (6) ochlocracy (which is “mob-rule” or degenerative democracy).

While Polybius has six steps, he actually believes in fewer government forms than Plato. Each even-numbered option is simply the degenerative form of the preceding odd number. So, a tyrannical kingship is the degenerative form of monarchy. Democracy is the virtuous preceding form until ochlocracy. Thus, we note three primary positive governments: monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. Rule-by-one, rule-by-few, and rule-by-many. Likewise, we can see the three degenerative forms as tyranny, oligarchy, and ochlocracy. Likewise, a rule-by-one, rule-by-few, and rule-by-many framework.

How do these political regimes cycle through one another? In direct quotation from The Histories, Polybius states:

Now the first of these to come into being is monarchy, its growth being natural and unaided; and next arises kingship derived from monarchy by the aid of art and by the correction of defects. Monarchy first changes into its vicious allied form, tyranny; and next, the abolishment of both gives birth to aristocracy. Aristocracy by its very nature degenerates into oligarchy; and when the commons inflamed by anger take vengeance on this government for its unjust rule, democracy comes into being; and in due course the license and lawlessness of this form of government produces mob-rule to complete the series. The truth of what I have just said will be quite clear to anyone who pays due attention to such beginnings, origins, and changes as are in each case natural. For he alone who has seen how each form naturally arises and develops, will be able to see when, how, and where the growth, perfection, change, and end of each are likely to occur again.[vi]

This transition is important, as are his concluding words. We have to be able to see how each form arises and develops to gauge whether they are likely to occur again and how to stop them. This is where the particular regime cycle of collapse will later be relevant. After this description of government trends, Polybius dedicates the next few pages to providing even more explicit detail over how this transition occurs.

To summarize these next few pages: Polybius believes a benevolent dictatorship will naturally begin under monarchy. However, over time, the hereditary passing down of power will result in the children of the monarch taking power, who will abuse this power as an absolute dictator. The heirs will not always be benevolent. Thus, their kingship eventually results in tyranny. The aristocrats grow weary of the tyrants and overthrow them, leading to aristocracy. The individuals in charge of the aristocracy eventually abuse their powers to amass wealth and degenerate behavior leading to oligarchy, which attracts the ire of the population. When this happens, the population fights back to take control over the entire system through democratic means for reasons identical to Plato’s five regimes model. They cannot trust the king nor the aristocrats, so they put the power into their own hands. After enough time passes after this occurred, the children of the nation will grow up entitled and without the knowledge or understanding of the sacrifice it took to lead them to liberty. The children of the nation will not understand the freedom, equality, or economic prosperity that the system has given them and they will simply demand more and more. Their own downfall is their own birth privilege. They’ve become accustomed to what they’ve been given, which will make them seek excess. This behavior will manifest as mob rule, as they use mob tactics to fulfill their demands. Living off others’ property will result in even further plundering, taken to an extreme. This will lead the citizens to seek yet another “benevolent” monarch master as the situation deteriorates. Any form of order, even a tyrannical one, is preferential to mob rule chaos. This will cause the citizens to be conditioned to desire and fight for the demagogues under the false guise of order or equality. Chaos ensues, and the state goes full circle back to an absolute ruler.

Polybius’s anacyclosis continues to be just as relevant today as it was during his own time. His work was revolutionary and used as historical precedent by dozens of other notable authors throughout history. A couple notable examples of those who have used Polybius’s works include Francesco Sansovino (an Italian historian and statesman considered one of the major political writers of the Italian Renaissance) in his renaissance work and John Adams (A Founding Father of the United States) in his “Defence of the Constitution” work.

Let’s start with Francesco. In Paul Grendler’s account of Francesco, he states the following:

Sansovino viewed the growth and decline of states in terms of Polybius’ anacyclosis. The initially good government of one man, monarchy, became a tyranny. Then the state was renewed by the efforts of a few good men who made it an aristocracy. This in turn decayed into oligarchy and was replaced by democracy which became mob rule which, in turn was supplanted by one-man rule as the cycle continued. Sansovino noted that worthy men attempted unsuccessfully to establish principates or republics to endure a thousand years. The reasons for failure were twofold. By their nature all human institutions carried within themselves the seeds of corruption which were human excesses and disorders. Second, one could not provide for everything. The accidents which befell states were so many and so diverse that it was impossible to provide against, or to correct, all of them.[vii]

Two important pieces we can take from this account are the failings of human institutions and that one cannot provide for everything at the onset. Both items we address through our framework. The institutional issue is addressed in the sensitive cultural marker and cultural chapters. The inability to protect against all possibilities issue is corrected through various contributor remedies scattered throughout all the chapters. Sansovino’s account is incredibly important because it was the inspiration for what created the most powerful tool that our framework provides: the “nuclear option”. This amendment corrects both of Sansovino’s main points against thousand-year regimes. This is addressed in later chapters.

His account also notes the importance of worthy men in the formation of any government framework. Worthy men must be at the helm and to the benefit of all men.

Grendler goes on to say:

Sansovino formulated a simple pragmatic resolution which assumed that men would continue to live the vita civile and which justified the study of history. Neither very pessimistic nor excessively optimistic, Sansovino’s views reflected Italian political reality. He did not share the hope of Polybius and Machiavelli that a mixed constitution would check the cycle, but he believed that men normally could control their own affairs and learn from the experience of others.

Sansovino found worth in the Polybius model of anacyclosis because it generally aligned with his in-depth study of history. He correctly noted that a mixed constitution alone would not correct the cycle, something that Polybius and Machiavelli lacked. While beneficial, this mixed constitution will not solve all the problems. He did, however, believe there were ways out of the cycle through the study of history and the education of men. Men must learn from the experience of others through tradition, the study of history, and the involvement of vanguards.

Even in the much more recent future, powerful political figures have found use in the Polybius model. John Adams, in his Defence of the Constitution, wrote the following:

Polybius thinks it manifest, both from reason and experience, that the best form of government is not simple, but compounded, because of the tendency of each of the simple forms to degenerate; even democracy, in which it is an established custom to worship the gods, honour their parents, respect the elders, and obey the laws, has a strong tendency to change into a government where the multitude have a power of doing whatever they desire, and where insolence and contempt of parents, elders, gods, and laws, soon succeed.[viii]

Does this sound familiar? Ironically enough, it sounds exactly like what has happened in the United States already. Adams is discussing cultural degradation in this paragraph, which has undeniably occurred. Both Polybius and Adams understand the importance of traditions, family structures, law and order, and proper cultural controls. All things that the rule-by-many cannot contain. We had a compound government, but it did not save us forever.

Adams goes on to address the steps of anacyclosis:

From whence do governments originally spring? From the weakness of men, and the consequent necessity to associate, and he who excels in strength. and courage, gains the command and authority over provisions, differing little in their clothes or tables from the people with whom they passed their lives, they continued blameless and unenvied. But their posterity, succeeding to the government by right of inheritance, and finding every thing provided for security and support, they were led by superfluity to indulge their appetites, and to imagine that it became princes to appear in a different dress, to eat in a more luxurious manner, and enjoy, without contradiction, the forbidden pleasures of love. The first produced envy, the other resentment and hatred. By which means kingly government degenerated into tyranny.

At the same time a foundation was laid, and a conspiracy formed, for the destruction of those who exercised it; the accomplices of which were not men of inferior rank, but persons of the most generous, exalted, and enterprizing spirit; for such men can least bear the insolence of those in power. The people, having these to lead them, and uniting against their rulers, kingly government and monarchy were extirpated, and aristocracy began to be established, for the people, as an immediate acknowledgment to those who had destroyed monarchy, chose these leaders for their governors, and left all their concerns to them.

These, at first, preferred the advantage of the public to all other considerations, and administered all affairs, both public and private, with care and vigilance. But their sons having succeeded them in the same power, unacquainted with evils, strangers to civil equality and liberty, educated from their infancy in the splendor of the power and dignities of their parents, some giving themselves up to avarice, others to intemperance, and others to the abuse of women, by this behaviour changed the aristocracy into an oligarchy.

Their catastrophe became the same with that of the tyrants; for if any person, observing the general envy and hatred which these rulers have incurred, has the courage to say or do any thing against them, he finds the whole body of the people inspired with the same passions they were before possessed with against the tyrant, and ready to assist him. Thereupon they put some of them to death, and banish others; but dare not, after that, appoint a king to govern them, being still afraid of the injustice of the first; neither dare they entrust the government with any number of men, having still before their eyes the errors which those had before committed: so that having no hope, but in themselves, they convert the government from an oligarchy to a democracy, and cake upon themselves the care and charge of public affairs. And as long as any are living, who felt the power and dominion of the few, they acquiesce under the present establishment, and look upon equality and liberty as the greatest of blessings. But when a new race of men grows up, these, no longer regarding equality and liberty, from being accustomed to them, aim at a greater share of power than the rest, particularly those of the greatest fortunes, who, grown now ambitious, and being unable to obtain the power they aim at by their own merit, dissipate their wealth, by alluring and corrupting the people by every method; and when, to serve their wild ambition, they have once taught them to receive bribes and entertainments, from that moment the democracy is at an end, and changes to force and violence. For the people, accustomed to live at the expence of others, and to place their hopes of a support in the fortunes of their neighbours, if headed by a man of a great and enterprizing spirit, will then have recourse to violence, and getting together, will murder, banish, and divide among themselves the lands of their adversaries, till, grown wild with rage, they again find a master and a monarch.

This is the rotation of governments, and this the order of nature, by which they are changed, transformed, and return to the same point of the circle.

Adams lived nearly two thousand years after Polybius but came to the same conclusions on the cycle of regime change. Adams tried to create a system that would prevent this from happening, but as we read his theory, we can draw perfect parallels with modern America. These trends occur in anacyclosis innately because of human nature. We cannot change the nature of humans, so the only way to address the problem is to change the entire framework that we are residing within to properly account for that human nature.

He notes that the rule-by-many form generally falls because the new generations are not brought up appropriately and a certain category of men who “aim at a greater share of power than the rest” form. This was Adam’s recognition to the centralizer problem. This is a major recurring theme throughout the historical texts. Any framework that is to be resilient to the cycle must not have the same weaknesses present in the rule-by-many form (allowances given to centralizers).

John Adams also had the following to say on the correction of the cycle (continued from the same source):

But perhaps it might be more exactly true and natural to say, that the king, the aristocracy, and the people, as soon as ever they felt themselves secure in the possession of their power, would begin to abuse it. In Mr. Turgot’s single assembly, those who should think themselves most distinguished by blood and education, as well as fortune, would be most ambitious; and if they found an apparition among their constituents to their elections, would immediately have recourse to entertainments, secret intrigues, and every popular art, and even to bribes, to increase their parties. This would oblige their competitors, though they might be infinitely better men, either to give up their pretensions, or to imitate these dangerous practices. There is a natural and unchangeable inconvenience in all popular elections. There are always competitions, and the candidates have often merits nearly equal. The virtuous and independent electors are often divided: this naturally causes too much attention to the most profligate and unprincipled, who will sell or give away their votes for other considerations than wisdom and virtue. So that he who has the deepest purse, or the fewest scruples about using it, will generally prevail.

It is from the natural aristocracy in a single assembly that the first danger is to be apprehended in the present state of manners in America; and with a balance of landed property in the hands of the people, so decided in their favour, the progress to degeneracy, corruption, rage, and violence, might not be very rapid; nevertheless it would begin with the first elections, and grow faster or slower every year. Rage and violence would soon appear in the assembly, and from thence be communicated among the people at large.

The only remedy is to throw the rich and the proud into one group, in a separate assembly, and there tie their hands; if you give them scope with the people at large, or their representatives, they will destroy all equality and liberty, with the consent and acclamations of the people themselves. They will have much more power, mixed with the representatives, than separated from them. In the first case, if they unite, they will give the law, and govern all; if they differ, they will divide the state, and go to a decision by force. But placing them alone by themselves, the society avails itself of all their abilities and virtues; they become a solid check to the representatives themselves, as well as to the executive power, and you disarm them entirely of the power to do mischief.

Adams notes numerous important items in this brief text. First, he mentions the issue that virtuous and independent electors are often divided and that the “unprincipled” will generally sell or give away their votes by using them unwisely. So, whoever is a financial centralizer or doesn’t mind bankrupting the nation in the pursuit of power, will always win elections. We take this threat seriously because it seems apparent in nearly every failing rule-by-many form. We correct it through our contributor voting system and order system.

The account of Adams is interesting because it recognizes a massive threat that had otherwise gone undetected by many other anacyclosis researchers. Specifically, “the rich and the proud” line in the last paragraph. He notices how quickly a small group can degrade the whole. He states this group should be “a separate assembly, and there tie their hands.” So, they should not only be separated but restrained as well. Much of our work is on doing just this. Whenever we address centralizer groups, we are directly addressing this issue.

Adams also addressed the issues of weak men, the need for a compound government, removing cultural degeneracy, averting mob rule, and the necessity of virtue. Things that are all essential to stopping anacyclosis, given historical trends and research accounts. His words are valued and are all implemented by Enclavism in some manner.

John Adams was not the only American Founding Father to speak on the subject. Another notable individual was George Washington himself. He gave a farewell address prior to his retirement with the following statements:

This government, the offspring of our own choice, uninfluenced and unawed, adopted upon full investigation and mature deliberation, completely free in its principles, in the distribution of its powers, uniting security with energy, and containing within itself a provision for its own amendment, has a just claim to your confidence and your support. Respect for its authority, compliance with its laws, acquiescence in its measures, are duties enjoined by the fundamental maxims of true liberty. The basis of our political systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their constitutions of government. But the Constitution which at any time exists, till changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole people, is sacredly obligatory upon all. The very idea of the power and the right of the people to establish government presupposes the duty of every individual to obey the established government.[ix]

This section is important. In it, Washington addresses the issue of having a changeable constitution, but one that can only be changed under the right conditions. He states that the constitution can only be changed by an “explicit and authentic act of the whole people.” Which is definitely not provided in modern America. A constitution could only be changed by the people if it were approved with numerous safeguards that could not be subverted. Also, the constitution has lacked power in America because of the rejection of originalist legal interpretations (meaning it can be changed by a cultural judiciary, not the entirety of its people) and the inability of the people to hold the political centralizer accountable to that constitution. Additionally, the constitution must be obligatory to all. It is not negotiable or removable by any centralizer. Our framework remedies each of these problems.

Washington goes on to say:

Towards the preservation of your government, and the permanency of your present happy state, it is requisite, not only that you steadily discountenance irregular oppositions to its acknowledged authority, but also that you resist with care the spirit of innovation upon its principles, however specious the pretexts. One method of assault may be to effect, in the forms of the Constitution, alterations which will impair the energy of the system, and thus to undermine what cannot be directly overthrown. In all the changes to which you may be invited, remember that time and habit are at least as necessary to fix the true character of governments as of other human institutions; that experience is the surest standard by which to test the real tendency of the existing constitution of a country; that facility in changes, upon the credit of mere hypothesis and opinion, exposes to perpetual change, from the endless variety of hypothesis and opinion; and remember, especially, that for the efficient management of your common interests, in a country so extensive as ours, a government of as much vigor as is consistent with the perfect security of liberty is indispensable. Liberty itself will find in such a government, with powers properly distributed and adjusted, its surest guardian. It is, indeed, little else than a name, where the government is too feeble to withstand the enterprises of faction, to confine each member of the society within the limits prescribed by the laws, and to maintain all in the secure and tranquil enjoyment of the rights of person and property.

George Washington noted numerous very key trends of an anacyclosis-resistant government. He addressed the importance of stopping political partisanship (which causes division, especially when it is geographical), of stopping too far-out cultural anomalies appearing throughout the nation (that would produce geographic division), of a mixed government and constitution, of the importance of a proper morality, and of a proper distribution of power. All essential characteristics of preserving a national soul through the system.

Later in the speech, Washington also addresses the serious threat of foreign involvement and foreign influence on republics. He states:

Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me, fellow-citizens) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake, since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government.

Foreign influence is a massive red flag for any rule-by-many government. Foreign centralizers or other provocative agents can help the domestic centralizers acquire a base of power to further exploit. In extreme cases, it can create a type of vassal state rule-by-few where the foreigner indirectly controls the “representatives” of the many. Careful watch must be placed on the foreign arena for any sustainable system.

All of these items are included in our theory of Enclavism but with far higher protections than the historic America was provided with. We take these items and expand on them in multitudes.

The reason the United States was a successful republic for a period of time is likely because of the actions of the Founding Fathers in implementing some of these beliefs. They helped, but clearly did not fully resolve, the issue of anacyclosis.

Too many loopholes still existed in the American framework even though the founders discussed them in-depth. Many key items they desired were never successfully implemented. For example, John Adams’s “tying of the hands” never got implemented. Neither did Washington’s distrust of foreign involvement get the proper credit it deserved.[x] These are only a couple of the dozens of safeguards that were left behind in the implementation of the American Republic.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, in 54 B.C., in his work “The Republic of Cicero” even had some things to mention on the topic. Regretfully, we are missing some of his key work due to the loss of the historical documents, but we do have some preserved statements from Cicero:

… and this great mischief arises whether under the rule of the better class, or under a tyrannical faction, or under the regal government; and even frequently under the popular form. At the same time from the various forms of government of which I have spoken, something excellent is wont to emanate. For the changes and vicissitudes in public affairs, appear to move in a circle of revolutions; which when recognized by a wise man, as soon as he beholds them impending, if he can moderate their course in the administration of affairs, and restrain them under his control; he acts truly the part of a great citizen, and almost of a divine man. Therefore I think a fourth kind of government, moderated and mixed from those three of which I first spoke, is most to be approved.[xi]

In this, Cicero is stating that all three forms (rule-by-many, rule-by-one, rule-by-few) are less than desirable. A fourth, being a mixture of the three, is desired. In several respects, this is what Enclavism does.

Additionally, Cicero notes how those leaders who can withstand the circle of revolutions are wise men, perhaps even divine men. This was the power of the cycle, especially during Cicero’s time: that it might take a divine man to stop it within the context of the current frameworks. He goes on:

And this I say of these three kinds of government, not of the agitations and disturbances incidental to them, but of their tranquil and regular state. Those varieties are principally remarkable for the defects I have alluded to. Then they have other pernicious failings, for every one of these governments is travelling a dangerous road, bordering on a slippery and precipitous path.

In short, Cicero is saying all the legacy frameworks will collapse eventually. He goes on to recommend a way to correct it:

For as in stringed instruments or pipes, as well as in singing with voices, a certain harmony is to be formed with distinct sounds, an interruption to which cannot be borne by refined ears; this kindred and harmonious concert being produced by the modification of dissimilar voices. So a government temperately organized from the upper, the lower and middle orders blended together, harmonizes like music by the agreement of dissimilar sounds. And that which in song is called by musicians, harmony, is concord in a state; the strongest and best bond of safety in every republic; yet which without justice cannot be preserved.

Hierarchical harmony. An essential element of any sustainable state. Cicero noted some interesting elements of a sustainable government all the way back in 54 BC. This is how long the cycle has been occurring and how long humanity has refused to learn from history.

Cicero, in De republica, speaks in-depth on a few key topics. These topics include a well-regulated mixture of the three government forms (no strict democracy or rule-by-many), the need for a proper distribution of national hierarchy (upper, middle, and lower. Meaning to not seek out “equality” or similar agents against a natural order), and the importance of understanding the “regular curving path” from which governments follow.

These items are equally important, as more modern republics have demonstrated. If any class becomes too powerful over the others, massive problems form. If any of the government forms are left entirely to their own devices, they will degrade. Addressing these items are key issues of addressing anacyclosis, and what future political theorists had desired to expand upon.

Other more recent historical figures, such as Machiavelli, Giambattista Vico, Julius Evola, and Montesquieu, have noted this trend as well.

Starting with Montesquieu:

Book 8. On the corruption of the principles of the three governments.

Chapter 2. On the corruption of the principle of democracy.

The principle of democracy is corrupted not only when the spirit of equality is lost but also when the spirit of extreme equality is taken up and each one wants to be equal to those chosen to command. So the people, finding intolerable even the power they entrust to the others, want to do everything themselves: to deliberate for the senate, to execute for the magistrates, and to cast aside all the judges.[xii]

The above paragraph addresses the issue of the nonmerit effect in rule-by-many forms and the issue of equality. Equality becomes a desirable trait in a democracy, but it is never a practical trait that can sustain itself. It rejects the natural order and traditional hierarchy of humanity. This is especially important regarding high-profile societal positions, such as the political class. When the less-than-worthy fill these roles, the nation will degrade rapidly. It is essential that those “chosen to command” are solidified within their positions.

Montesquieu goes on:

Corruption will increase among those who corrupt, and it will increase among those who are already corrupted. The people will distribute among themselves all the public funds; and, just as they will join the management of business to their laziness, they will want to join the amusements of luxury to their poverty. But given their laziness and their luxury, only the public treasure can be their object.

One must not be astonished to see votes given for silver. One cannot give the people much without taking even more from them; but, in order to take from them, the state must be overthrown. The more the people appear to take advantage of their liberty, the nearer they approach the moment they are to lose it. Petty tyrants are formed, having all the vices of a single one. What remains of liberty soon becomes intolerable. A single tyrant rises up, and the people lose everything, even the advantages of their corruption.

Therefore, democracy has to avoid two excesses: the spirit of inequality, which leads it to aristocracy or to the government of one alone, and the spirit of extreme equality, which leads it to the despotism of one alone, as the despotism of one alone ends by conquest.

The issues that Montesquieu brings to the forefront are certainly viable contentions. Any system that seeks to fix their cycle permanently must invariably address the issues he raises, which are virtue, the soul of the people, corruption, and the issue of “votes for silver” (the funds of contributors being used to buy the votes of noncontributors). All relevant pieces of anti-anacyclosis.

There are two major topics here to point out.

The first is that Montesquieu correctly notices the effect of bad voters in democracy. This should be a recurring theme at this point, but he specifically addresses the problem to a fuller extent. This gives us a couple of important lessons. First, those who have the highest say in voting must be those who contribute the most, to avoid the issues of problematic voters. This is the platform for our contributor voting system called “oversight voting”. Noncontributors must be discouraged in order to halt their potential dependency-laden corruption. Second, the politicians must never be put in a position where they are incentivized for short-term gain to partake in corrupt acts. They must never have a strong incentive to “buy out” votes of noncontributors. The incentive must always be placed on pleasing contributors. Neither should they feel constant pressure from the lower societal arenas with regard to the potential loss of their position. Their positions must be somewhat similar to the positions of a rule-by-few, so they are more interested in effective ruling than they are in struggling to keep their power through the use of corruption, short-term policies, mobs, or low-information voters. We accomplish this through our Order system.

The second topic is on equality. The nation cannot sustain itself if it becomes too unequal because then it would become or be at risk of a rule-by-few. This is offset by our tackling of centralizers, especially of the isolated class. But the problem is just as bad if looked at inversely. If the nation becomes too equal, then merit will take a backseat and despotism arises. This means that overreaching equality must be thoroughly rejected and shut down, which is a component of our cultural baseline.

Proceeding onward to Julius Evola, a traditionalist. He draws on the work related to de Gobineau, René Guénon, and Nietzsche. Evola states in his work “Revolt Against the Modern World”:

Among various writers, de Gobineau is the one who probably better demonstrates the insufficiency of the majority of the empirical causes that have been adduced to explain the decline of great civilizations. He showed, for instance, that a civilization does not collapse simply because its political power has been either broken or swept away: “The same type of civilization sometimes endures even under a foreign occupation and defies the worst catastrophic events, while some other times, in the presence of mediocre mishaps, it just disappears”. Not even the quality of the governments, in the empirical (namely, administrative and organizational) sense of the word, exercises much influence on the longevity of civilizations. De Gobineau remarked that civilizations, just like living organisms, may survive for a long time even though they carry within themselves disorganizing tendencies in addition to the spiritual unity that is life of the one common Tradition […] Not even the so-called corruption of morals, in its most profane and moralistically bourgeois sense, may be considered the cause of the collapse of civilizations; the corruption of morals at most may be an effect, but it is not the real cause. In almost every instance we have to agree with Nietzsche, who claimed that wherever the preoccupation with “morals” arises is an indication that a process of decadence is already at work; the mos of Vico’s “heroic ages” has nothing to do with moralistic limitations. The Far Eastern tradition especially has emphasized the ideas that morals and laws in general (in a conformist and social sense) arise where “virtue” and the “Way” are no longer known […] Rites, institutions, laws, and customs may still continue to exist for a certain time; but with their meaning lost and their “virtue” paralyzed they are nothing but empty shells. Once they are abandoned to themselves and have become secularized, they crumble like parched clay and become increasingly disfigured and altered, despite all attempts to retain from the outside, whether through violence or imposition, the lost inner unity. As long as a shadow of the action of the superior element remains, however, and an echo of it exists in the blood, the structure remains standing, the body still appears endowed with a soul, and the corpse—to use to image employed by de Gobineau—walks and is still capable of knocking down obstacles in its path. When the last residue of the force from above and of the race of the spirit is exhausted, in the new generations nothing else remains; there is no longer a riverbed to channel the current that is now dispersed in every direction. What emerges at this point is individualism, chaos, anarchy, a humanist hubris, and degeneration in every domain. The dam is broken. Although a semblance of ancient grandeur still remains, the smallest impact is enough to make an empire or state collapse and be replaced with a demonic inversion, namely, with the modern, omnipotent Leviathan, which is a mechanized and “totalitarian” collective system.[xiii]

Evola, de Gobineau, and Nietzsche all bring up important points regarding the spiritual part of the life and death of civilizations. Even if we were to build the most flawless system in theory, if that system was heralded by a people who lose their “Way”, it is all for nothing. Any framework we create must take special measures to ensure that this traditional, metaphysical, “race of the spirit” part is placed at the forefront of importance. We address this by addressing what we call the soul of the nation. Where this national soul is an incorporeal essence of a nation, similar to that of an individual, that demonstrates a combination of the mind and spirit on a metaphysical level to produce the very “being” of the nation. It is the combination of the spiritually animating and the language, religion, morality, history, wisdom, mind, spirit, and everything else that makes up that essence of a people.

It is not enough to focus on the effects of decline, like morals and system weaknesses; we must also ensure our framework and system set up a linear pathway to the continuation of this soul of the nation. No form can do this by itself, but they can guarantee that it does nothing to inhibit the vanguard spirit and promotes every positive aspect that is necessary for the soul to thrive and sustain. It can also prevent those who so often target the soul to weaken the entire system. We can, and must, fortify the dam. This is one of our most essential tasks in crafting the Enclavist doctrine.

In later chapters, Evola also addresses the cycle of political governance. He continues:

Once the apex disappeared, authority descended to the level immediately below, that is, to the caste of warriors [from the Traditional apex]. The stage was then set for monarchs who were mere military leaders, lords of temporal justice and, in more recent times, political absolute sovereigns. In other words, regality of blood replaced regality of the spirit. […] This was essentially the age and the cycle of the great European monarchies. Then a second collapse occurred as the aristocracies began to fall into decay and the monarchies to shake at the foundations; through revolutions and constitutions they became useless institutions subject to the “will of the nation,” and sometimes they were even ousted by different regimes. […] Together with parliamentary republics the formation of the capitalist oligarchies revealed the shift of power from the second caste (the warrior) to the modern equivalent of the third caste (the mercantile class). The kings of coal, oil, and iron industries replace the previous kings of blood and spirit. […] At this time the social bond was no longer a fides of a warrior type based on relationships of faithfulness and honor. Instead, it took on a utilitarian and economic character; it consisted of an agreement based on personal convenience and on material interest that only a merchant could have conceived. Gold became a means and a powerful tool; those who knew how to acquire it and to multiply it (capitalism, high finance, industrial trusts), behind the appearances of democracy, virtually controlled political power and the instruments employed in the art of opinion making. […] Finally, the crises of bourgeois society, class struggle, the proletarian revolt against capitalism, the manifesto promulgated at the “Third International” (or Comintern) in 1919, and the correlative organization of the groups and the masses in the cadres proper to a “socialist civilization of labor”—all these bear witness to the third collapse, in which power tends to pass into the hands of the lowest of the traditional castes, the caste of the beasts of burden and the standardized individuals.[xiv]

Evola related the cycle of political collapse to that of the Kali Yuga. He noted how the cycle of structural collapse corresponded directly to the cycle of spiritual collapse and the transitioning of castes within the nation-state. Once focused on divine right and a traditional leadership, this declines to the warrior caste, which further declines to the merchant caste, and culminates in the decline to the proletarian caste having absolute power. It’s important to take into consideration that this view is one of a civilizational outlook, not specifically intra-national. The civilization as a whole follows this path. This process, Evola states, cannot be stopped. We can only go forward through it.

While we do not hold exactly to his linear progression, the recognition of the transition of power between the castes during civilization descent is not something we refute. Both the traditional and the warrior positions are given high importance within our framework, to not allow the leadership to degrade to one of the merchant or proletarian caste which has provoked many of the issues we will later attempt to rectify (individualism, capitalistic exploitation, wealth as a virtue, isolated class centralization, et cetera).

Evola also noticed how the isolated class becomes the main political driver during the mercantile stage and how the centralizers still hold absolute power, but all while residing under the illusion of democracy. This reality, once uncovered, leads directly to the mob effect, or what he calls the proletarian revolt against capitalism. Both factors that we attempt to remedy. We also fully agree with his position that there is no way to stop this degradation given our current positioning within it, besides going full force ahead through it.

Moving on to Giambattista Vico, who was a vigorous proponent of the monarchy form of governance (rule-by-one). He states:

The monarchical form was introduced in accordance with this eternal natural royal law, felt by all the nations which recognize in Augustus the founder of the Roman monarchy. … Pomponius, in his brief history of Roman law, discussing the royal law of which we speak, described it for us in the wellconsidered phrase: rebus ipsis dictantibus, regna condita “kingdoms were founded at the dictation of things themselves”.

This natural royal law is conceived under this natural formula of eternal utility: Since in the free commonwealths all look out for their own private interests, into the service of which they press their public arms at the risk of ruin to their nations, to preserve the latter from destruction a single man must arise, as Augustus did at Rome, and take all public concerns by force of arms into his own hands, leaving his subjects free to look after their private affairs and after just so much public business, and of just such kinds, as the monarch may entrust to them. Thus are the peoples saved when they would otherwise rush to their own destruction. In this truth the professors of modern law concur when they say that universitates sub rege habentur loco privatorum–”corporations are treated as private persons under the king”–because the majority of the citizens no longer concern themselves with the public welfare. Tacitus, most learned in the natural law of nations, points out as much in his Annals within the family of the Caesars itself, by this order of human civil ideas: As the death of Augustus became imminent, pauci bona libertatis incassum disserere–”a few spoke in vain of the blessings of liberty”; as soon as Tiberius came, omnes principis iussa ad spectare–”all looked to the commands of the emperor”; under the three subsequent Caesars first came incuria or indifference and finally ignorantia reipublicae tanquam alienae, ignorance of public affairs as something foreign. Thus, as the citizens have become aliens in their own nations, it becomes necessary for the monarchs to sustain and represent the latter in their own persons. Now in free commonwealths if a powerful man is to become monarch the people must take his side, and for that reason monarchies are by nature popularly governed: first through the laws by which the monarchs seek to make their subjects all equal; then by that property of monarchies whereby sovereigns humble the powerful and thus keep the masses safe and free from their oppressions; further by that other property of keeping the multitude satisfied and content as regards the necessaries of life and the enjoyment of natural liberty; and finally by the privileges conceded by monarchs to entire classes (called privileges of liberty) or to particular persons by awarding extraordinary civil honors to men of exceptional merit (these being singular laws dictated by natural equity). Hence monarchy is the form of government best adapted to human nature when reason is fully developed, as we have said before.[xv]

Vico is right in many contexts, but has lacked the historical insight regarding the damage that rule-by-one’s can cause and the inability for certain populations to truly “take his [the one’s] side” to be popularly governed.

For our use, what Vico uncovered was the fact that the average citizen that only looks out for their own private interests is the problem, which is certainly true. This is why our political class must demonstrate the exact opposite of this and all institutions in the nation should be run strictly by merit. While also sharing oversight by those not seeking self-interest. Additionally, the king benefitted the nation by keeping the other powerful interests in check, so they did not disturb the population. Our political class must do the same. Further, we must shift the societal focus from sole private individualism to a more communitarian approach. Our structure and Order system aim to correct this glaring issue with the rule-by-many framework, without having to resort to trying to stabilize a rule-by-one (totalitarian) approach.

Let us move on to Niccolò Machiavelli. In History of Florence, Machiavelli stated the following:

It may be observed, that provinces amid the vicissitudes to which they are subject, pass from order into confusion, and afterward recur to a state of order again; for the nature of mundane affairs not allowing them to continue in an even course, when they have arrived at their greatest perfection, they soon begin to decline. In the same manner, having been reduced by disorder, and sunk to their utmost state of depression, unable to descend lower, they, of necessity, reascend; and thus from good they gradually decline to evil, and from evil again return to good. The reason is, that valor produces peace; peace, repose; repose, disorder; disorder, ruin; so from disorder order springs; from order virtue, and from this, glory and good fortune. Hence, wise men have observed, that the age of literary excellence is subsequent to that of distinction in arms; and that in cities and provinces, great warriors are produced before philosophers. Arms having secured victory, and victory peace, the buoyant vigor of the martial mind cannot be enfeebled by a more excusable indulgence than that of letters; nor can indolence, with any greater or more dangerous deceit, enter a well regulated community. Cato was aware of this when the philosophers, Diogenes and Carneades, were sent ambassadors to the senate by the Athenians; for perceiving with what earnest admiration the Roman youth began to follow them, and knowing the evils that might result to his country from this specious idleness, he enacted that no philosopher should be allowed to enter Rome.[xvi]

Polybius noted the importance of the political regime. Machiavelli noted the importance of strong men. He also noted early Roman attempts to divert the cycle of collapse by focusing on strong men, strong government, aversion to foreigner integration, and not permitting philosophers in their midst (where philosophers are those that would inspire cultural and societal degradation—“men of words”). This was one tactic of many that ancient societies used in trying to break the cycle of collapse.

Machiavelli’s theory is closely related to the modern “Strong Men” theory and likely had its origins from it. The Strong Men theory is a simpler version of his words. It is the common saying: “Hard times create strong men. Strong men create good times. Good times create weak men. Weak men create hard times”.[xvii] The cycle then repeats. This is an oversimplification but an accurate rendition of the effect.

Niccolò’s theory, while not being as fully developed as Polybius’s, follows a similar pattern: good times lead toward prosperity, from prosperity toward indulgence, from indulgence toward weakness, from weakness toward evil, from evil toward conflict, from conflict toward strength, and from strength toward good times. Rinse, repeat.

Warriors, in the case of anacyclosis, are far more important than philosophers when considering practical political cycles. Just as strong, virtuous man is far more important to protect than degenerative men from a societal standpoint. This is the difference between the men of words versus the men of action. Understanding these intimate details about why the degeneration happens will be essential in stopping it. The men of action must always take precedence over the men of words.

Additionally, in Discourses, Machiavelli noted the importance of national hegemony, strong leadership, and aversion to foreign integration:

[…] But no time is given in the case of disorders in the State itself, which unless they be treated by some wise citizen, will always bring a city to destruction. From the readiness wherewith the Romans conferred the right of citizenship on foreigners, there came to be so many new citizens in Rome, and possessed of so large a share of the suffrage, that the government itself began to alter, forsaking those courses which it was accustomed to follow, and growing estranged from the men to whom it had before looked for guidance.[xviii]

Which provides further evidence of the necessity to preserve the “nation” element of the Three Essentials. If one alters the composition of the elements within the nation, it is only logical to recognize that the nation itself will likewise be fundamentally altered. This also demonstrates the need for strong and wise leadership, to avert disorders within the state itself.

Ryszard Legutko, a notable Polish statesman and professor of philosophy, summed up the historical greats’ positions, along with providing his own thoughts, in his book Demon in Democracy:

The argument of the ancient thinkers was simple, and it arose from an accurate observation, well-grounded in political experience, that most regimes are defective by being one-sided: that is, by going too much in one direction determined by the specificity of the group that exerts the predominant influence in the functioning of the system. This observation, one could say, anticipated Churchill’s view (or rather that Churchill’s view reiterated, in a slightly changed form, the classical insight). The ancients distinguished three basic types of regimes: monarchy (one-man rule), oligarchy, called sometimes aristocracy (minority rule), and democracy (majority rule). They regarded each of them as good in some aspects and deficient in others. Each system, then, while being superior to the alternatives, was also inferior to them. For example, the advantage of monarchy was that it simplified the decision-making process and gave it greater consistency; its disadvantage, among other things, was the danger of tyranny. The advantage of oligarchy was its educational elitism and its disadvantages a possible subordination of public interest to that of a minority group. The advantage of democracy was its representativeness and its disadvantages anarchy and factionalism.

A possible solution of the problem of one-sidedness was to mix the three types. One could therefore devise a political structure that combined monarchy, oligarchy, and democracy in such a way that each would foster the advantages and neutralize the disadvantages of the others. We would then have, for example, a democratic representativeness but at the same time some oligarchic-aristocratic institutions that would preserve a form of elitism as well as some form of monarchy guaranteeing the efficiency of governance. Such combination depended on the ingenuity of the politicians and the character of a particular society, and could produce a variety of hybrid political forms. When Cicero referred to this mixed regime, he used the name “res publica”. This was the beginning of a very important republican tradition in Western civilization.

In its modern versions, republicanism moved along complex paths, sometimes losing the original meaning (especially when used solely as a shorthand for revolutionary antimonarchism), but the main message given to it by the ancients was often preserved. The political community organized as a republic was a structure containing various elements, one being a democratic component. Even the American system, which today is regarded as the exemplary embodiment of representative democracy, was established as a hybrid construction. Some of the Founding Fathers regarded it as a major problem how to limit the rule of the demos and secure the proper role of the aristocratic element, whose responsibility would be the defense and propagation of ethical and political virtues. Tocqueville contemplated a similar problem, which seemed to him even more pressing, considering that he saw the advent of democracy as irresistible; in the new times that were approaching it then become a matter of utmost urgency to inject some aristocratic spirit into an ever more egalitarian society. [xix]

There is a lot to unpack in this short quotation. To begin, Legutko mentions the accurate observation of the ancients regarding the legacy rule-by forms going too far in their own direction. The issues with the current “hybrid” forms are that the power cycle and balance between the power centers is far off, leading to one extreme that permeates another. Slight democracy becomes a full-blown egalitarian and degenerate democracy, which is then a shorter skip to a rule-by-few due to its pure nature. The cycle of collapse in each form is between each of their full implementations. Therefore, if there are hybrid elements, those must be destroyed first to begin the process of anacyclosis. A pure rule-by-many egalitarian democracy will be the most decentralized variant of all, allowing easy access for centralizers to infiltrate and degenerate. Compared to that of a republic, which has rule-by-few elements, they must first take out the hybrid-nature.

Another interesting thing to note here is that only certain elements were made hybrid in the traditional republic form. Demos dominated. These aspects created a half-hearted hybrid in the form of the republic. Even the United States, which Legutko said is regarded as an exemplary embodiment of representative democracy, leaned far too heavily on the demos side. It needed far more elements of the rule-by-few and rule-by-one to sustain itself. However, if this ideal scenario had come to pass, the United States then wouldn’t have been classified as a rule-by-many. Therein lies the paradox of hybridization. We can seek hybrid forms all we want, but one of them must have at least a slight advantage over the others, which will then allow that dominant form to slowly homogenize its hybrid elements until it is pure. Once pure, it will degenerate in a traditional fashion. The only alternative is an altogether new option.

We need a new framework entirely, not a hybrid. In doing so, we can bring in components of each of the other forms, but then if they degenerate, they do not lean toward only one expression of a legacy framework. Our framework, for instance, could be called a rule-by-few, rule-by-one, or rule-by-many, depending on which component you are discussing. Even further, it could be called a hybrid of each within each element. Or more accurately, not a hybrid at all. Voting? A rule-by-many with a focus on a few where the majority can become that few through contributions. Politicians? A rule-by-few, with elements of a rule-by-one and oversight of a rule-by-many. Culture? A rule-by-one, where the one is a select few that anyone from the many may join with some effort. It seems complex now, but it will make sense in future chapters as we tie it all together. The takeaway is that our new form must not just be a plain hybrid but a different one altogether that even creates internal hybridization of the essential governmental elements. When we do this, we create what can only be defined as a “rule-by-contributor” because of the balancing elements it must entail to accurately capture each internal hybrid. At the end of it all, we must create a specialization for each element so that no pure legacy expression can be exploited.

Most of the Founding Fathers wanted stricter controls on demos, not more. They were right in that belief but unsuccessful in its implementation. The procedures that they put in the system did not suppress the demos elements forever. It is clear that modern America is now a full-blown liberal democracy, with a republic acting only in name (sometimes, not even that much). Which is why it has now begun rapid degeneration into a rule-by-few.

Finally, Legutko also mentions the problematic impact of political egalitarianism. Political egalitarianism is a method by which centralizers forcefully push for more rule-by-many elements at the expense of the hybrid elements by claiming to be in service of “equality” or “democracy” or some other meaningless buzzword. This, like many other language-controlled tools in a degenerating rule-by-many, is highly damaging to the hybrid elements that sustain it. When equality is the end goal and foundational myth, then destroying the surrounding elements that are meant to sustain the government is permitted. Respecting that there are social, economic, political, intellectual, and other differences between individuals must always triumph over political egalitarianism. Otherwise, the push for absolute democracy will push the nation right off a cliff. It is simple, the nation must have hierarchy.

Sir John Glubb also noticed similar trends as the preceding authors. In The Fate of Empires and Search for Survival, he wrote extensively about degenerating empires. A brief summary is followed:

While the stages of great nations could be debated, the trend is generally sound and in line with other historical figures. His theory on decadence, however, is spot-on, along with the recognition that it is internal factors, not external pressures, that bring about the decline of nations. They destroy themselves, as most other political theorists have noted. Correcting each of these is essential for any sustainable framework.

He also noted a general timespan of around 250 years for most empires. He tracked empires such as Assyria (859-612 BC), Persia (538-330 BC), Greece (331-100 BC), Roman Republic (260-27 BC), Roman Empire (27 BC-AD 180), Arab Empire (634-880 AD), Mameluke Empire (1250-1517 AD), Ottoman Empire (1320-1570 AD), Spain (1500-1750 AD), Romanov Russia (1682-1916 AD), Britain (1700-1950 AD), and others. His expertise was in the Arabian and British regions, but similar trends were noted in empires worldwide. While not all empires follow this linear path exactly, it can easily be argued that the majority do. There is definitely an average duration of recycling that occurs using the legacy forms, excluding the occasional exceptions to the trend.

Sir John Glubb recognized these empires were completely different in terms of ethnicity, culture, and about every other generalization you could classify them under, but they all lasted around the same time and died for the same reasons. Why? The cycle of collapse.

Let us briefly walk through his theory. The Age of Pioneers is when the nation is first forming and solidifying itself. It is marked by brave men and a constant fight for success and survival. After the nation is settled, these men of action change to seek riches. The Age of Conquest leads the nation to great riches, wealth, and power. During this stage and the first half of the Age of Commerce, the virtues of courage, patriotism, unity, and truthfulness are everywhere. The people are rough, hardy, proud, and strong. Duty is witnessed everywhere. Pride and honor are in the air.

Then, the descent begins. Courage and duty gradually decline in the nation because the nation has vast wealth that was gained during their conquests, and the traits that made these riches possible are regarded as no longer needed. Many times, they are even regarded as primitive. Greed becomes commonplace. Where the nation used to be focused on self-sacrifice and duty, the nation turns inward, and individualism takes hold. With it comes covetousness and avarice. The Age of Affluence is then ushered in. With it, the voice of duty is fully silenced. The young no longer desire honor or service, but they instead seek money. Education shifts and focuses on teaching random unfulfilling qualifications instead of creating brave patriots. Degeneracy and selfishness become near requirements to thrive.

The Age of Intellect follows and shifts the focus even further on descent. Philosophers overtake the sacrificial warriors. The men of action are replaced by the men of words. Internal strife increases significantly because of the increasing tension between different intellectuals and ideologies. Individuals reject the idea that the nation does not depend on loyalty and self-sacrifice, which is the hallmark of great nations in their early stages. Mental cleverness trumps virtue. Foreigners often arise in great numbers during this period, as the nation is still very wealthy but is now dominated by emotionally inclined “intellectuals.” The empire is less protective than their earlier counterparts and thus immigration can increase to extraordinary levels. Welfare-type programs and policies increase dramatically. As generally comes with extensive focuses on intellect without other proper outlets, pessimism and nihilism arise as well.

Finally, as all the virtues and beliefs that lead to their original victories vanish, the nation itself vanishes. The descent follows the Age of Intellect. The Age of Decadence marks the culmination of these effects and the nation-state eventually collapses. Pioneers are then needed to start again.

One of the main points that Sir Glubb makes that is incredibly important to grasp is that greed and individualism take over, instead of the original virtues that led to their apex in the Age of Affluence. The nation employs proper virtues and an honorable soul to become affluent but then becomes degraded after being rich for an extended amount of time. This is similar to most of the preceding authors’ analyses.

Glubb even noted trends as obvious today as the focus on how the conception of heroes shifts over time: where a nation once looked up to distinguished statesmen, military men, and literary geniuses, the nation now reveres athletes, singers, or actors. This small shift clearly signifies the cultural shift witnessed from a devotion to self-sacrifice, honor, and duty to one of wealth and fame. A shift from the positive to negative; from the higher to lower form.

No nation can survive that places money over courage. It’s simply not possible. This is why culture and a proper upbringing of children are so paramount. It’s also why nationalism and defense of the national population must play a large role in any sustainable framework. Both are far more important than economic function, individualism, or another self-focused trait. Men of words must also never be placed above men of action. The citizens must never be allowed to enter a state free of struggle, even if artificial solely for developmental purposes.

All of these are good examples of what occurs during this cycle of collapse. These shifting attitudes have occurred in every nation that has collapsed, from the Arabian Empire, to the Roman Empire, to Venezuela, to Zimbabwe, and even to the modern Western world. It happens everywhere.

Sir John Glubb also stated the following in the Fate of Empires:

Would it help? It is pleasing to imagine that, from such studies, a regular life-pattern of nations would emerge, including an analysis of the various changes which ultimately lead to decline, decadence and collapse. It is tempting to assume that measures could be adopted to forestall the disastrous effects of excessive wealth and power, and thence of subsequent decadence. Perhaps some means could be devised to prevent the activist Age of Conquests and Commerce deteriorating into the Age of Intellect, producing endless talking but no action.[xxi]

This sentiment is exactly what we are trying to do with Enclavism: use the historical realities to discover the life-patterns of nations to find a way to conquer this never-ending cycle. Plato, Aristotle, Polybius, and plenty of other important historical figures had also wished for the same objective. Attempting to find ways to stop the Age of Intellect, and even component pieces of the Age of Affluence, is key.

Henning Webb Prentis Jr. shared a similar opinion to that of Sir John Glubb. Prentis was an American industrialist who developed the “Prentis Cycle.” Much of his work is often misattributed to others such as Alexander Tytler or Alexis de Tocqueville, which likely includes the famous “Tytler Cycle” and “Fatal Sequence” theories. Both Tocqueville and Tytler expressed similar critical views of democracy, likely leading to the misattribution. The expanded Prentis Cycle is followed:

From bondage to spiritual faith; from spiritual faith to courage; from courage to freedom; from freedom to abundance; from abundance to selfishness; from selfishness to complacency; from complacency to apathy; from apathy to fear; from fear to dependency; and from dependency back to bondage once more.[xxii]

This cycle shares a familiar theme by this point. We see a powerful national soul leading the people out of tyranny, which degrades to excess and individualism, then further degrades to apathy and weakness, and ends in dependency and collapse. The focus on freedom, abundance, and individualism overtakes the necessary vanguard attributes of courage and the national soul. Any framework put in place to overcome this cycle must make sure it stops this distortion from occurring. Prentis spoke about this trend in relation to democratic government, but as we will soon see in the next section, it actually relates to both the cycle of collapse and anacyclosis.

A more modern work, The Collapse of Complex Societies by Joseph Tainter, is also worth mention. Tainter uses nearly two dozen cases of political collapse to create a model to evaluate how societies fall. He believes that collapse occurs because of diminishing marginal returns as the level of complexity of a state increases. This diminishment occurs in the realm of problem-solving capacity. As the state rises in power, it increases in managerialism and complexity. The state cannot retract in terms of complexity. Given enough time, the cost to maintain that state will exceed the cost of the resources that are necessary to solve their problems. Eventually, a shock occurs, and the state collapses due to this resource allocation failure. Tainter defines a complex society as one that has a lot of heterogeneity and centralization. Both of which are inevitable given the legacy frameworks and the cycle, as we have discussed. Both of which we would agree are also clear problems that directly impact anacyclosis. Tainter’s theory is of interest, but focuses more on the overall picture rather than the exact component pieces that we are trying to resolve. Still, the issues that he raises are accurate and worth consideration. We focus on correcting the reasons why increasing complexity, heightened managerialism, and diminishing marginal returns happen. As centralizers acquire more power and control, the marginal return provided by the centralized institutions diminishes. Their ability to solve societal-level problems decreases. This creates an unsustainable environment. An environment where a simple shock can create a cataclysmic result. We address each of these problems in future chapters.

Let’s move on to a few notable last mentions on the study of anacyclosis. A less relevant but still noteworthy account comes from Hesiod’s Five Ages and Ovid’s Four Ages, where they address a gradual descent of humanity to a rougher and more evil age. This generally aligns with the cycle of governance, even though they were speaking of the ages of man, instead of the ages of nations. Still, the theme and descent are similar, descending from a “Golden Age” to our current situation, the “Iron Age.” For the curious reader, they are worth looking into.

Another notable mention is the Yuga theory taken from Hinduism. The Pancharatra text, Vishnu Purana, explains this in great detail. Kali Yuga is the final (fourth) stage of the Yuga Cycles. It is believed that we are currently in this cycle, which is full of debauchery and conflict. The idea is that each Yuga’s length and their respective moral state is decreased by one fourth as each Yuga cycle transitions. Meaning that the length and the moral climate deteriorate more rapidly after each prior stage. Then the cycle repeats from the beginning. It is easy to relate these four cycles to the cycles of civilizations, governments, and the national souls of people. They start off strong and then deteriorate at a much more rapid pace the further on the cycle that they are. The same often occurs during anacyclosis. Degeneration is exponential, not linear.

Additionally, many of the afflictions mentioned within the Hindu text have been incredibly accurate, such as the disintegration of marriage, the totalitarianism of states, and the domination of money through all facets of life. Regarding the Hindu theory that we are currently living in the Kali Yuga, at least in terms of governmental deterioration, I would wholeheartedly concur. However, the timeline is debatable. Still, this provides the need for a traditional point when seeking sustainment, for this point rests itself further from accelerating degeneration.

It is of interest that even religions recognize the cycle of birth-death-rebirth, especially of moral and spiritual manners. We see this in all major world religions, from the resurrection of Christ[xxiii] to the Kali Yuga theories of Hinduism to Confucianism Yin-yang to Buddhist reincarnation and so forth. Perhaps the cycle we witness with all of these aspects of humanity is truly transcendent, but that is a topic for another time.

A more modern author, Peter Turchin, also has insightful books on the rise and fall of nations.[xxiv] Two works are worth particular mention. “War and Peace and War” argues that the formative years of great empires are due to their capacity for collective action (what we would call communitarianism and vanguard formation). Whereas internal conflict due to various factors, such as an isolated class and the proliferation of individualism, leads to the decline. Another one of his works, The Secular Cycles, finds four stages of anacyclosis. These stages are expansion, stagflation, crisis, and disintegration. There is a leading emphasis on population expansion during the expansion stage. In this work, he finds that eventually there are too many elites at the stagflation and crisis stage that are then forced to fight with each other, which shares similarities to our own theory regarding the centralizers. He proves the validity of this topic through mathematics, critical historical analysis, and statistical modeling.

Alexis de Tocqueville likewise has some excellent commentary on problems within democracy and the rule-by-many form, but is limited mostly to that framework. An understanding of his work, most notably Democracy in America, will be useful to us in the next chapter.[xxv]

Many other works, such as The Rise and Decline of Nations by Mancur Olson, The Decline of the West by Oswald Spengler, and Suicide of a Superpower by Patrick Buchanan, are also suitable reference materials for added study on the political cycle of collapse. Within this short list, Olson focuses on the economic components of collapse, Spengler concentrates on cultures evolving as organisms into civilizations and facing a repetitive flourish-to-decline cycle (through a spiritual death of the soul), and Buchanan pinpoints the religiosity and moral deterioration that coincided with the demographic destruction of the heritage Americans. We already have or will address each of these issues in this book, but for a deeper review these works are still recommended.

There are certainly plenty of other great works on this subject, but we have covered the majority of the prevailing theories. Still, other works can be helpful for further in-depth journeys into particular problems, places, or systems if they are of interest.[xxvi]

This concludes our review of the literature on anacyclosis. Now, picture an hourglass. When the government enters a new legacy political regime, it flips the hourglass to allow the sand to pour down. Some sand timers will be given a lot of sand; some will be given very little. Once the sands reach half, we have reached the degenerative stage of that government. Once the sand fully reaches the bottom, the next leader flips the hourglass and we enter the next regime. This cycle never ends.

During each degenerative stage, the people suffer. After each degenerative regime collapse, the virtuous citizens are left to pick up the pieces and try to rebuild, only to be placed in the exact same scenario whenever the next collapse comes about again. This cycle holds back humanity and destroys entire nations of people in the process.