Most Recent News

Popular News

What are the problems associated with occupational licensing? Is it a good or bad economic policy from an overall standpoint?

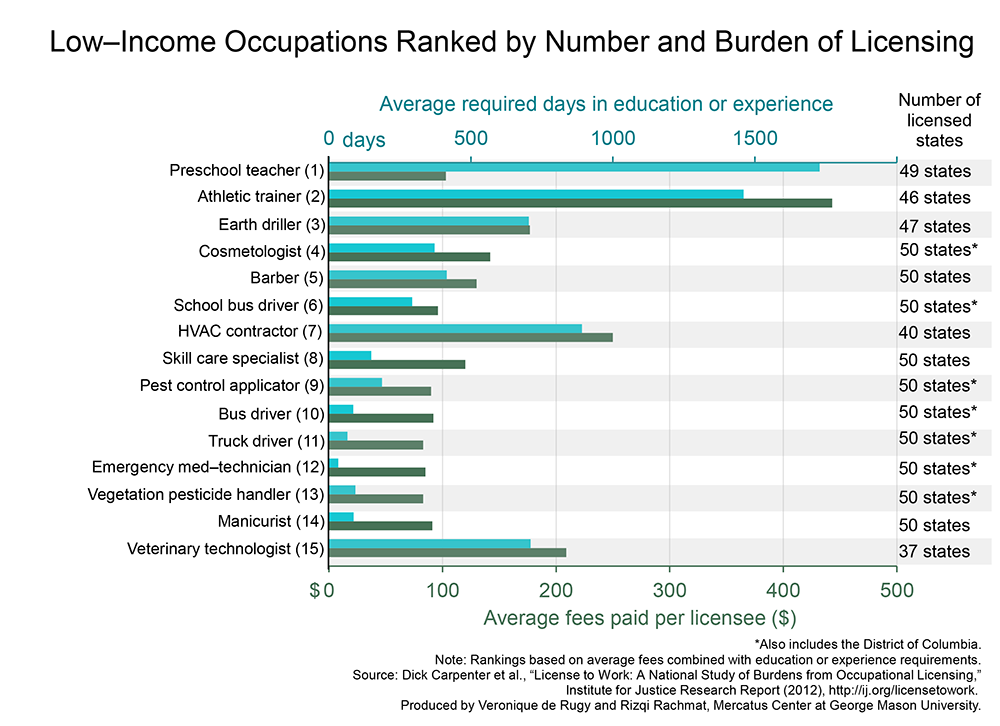

Occupational Licensing is a form of government regulation that requires individuals to pass some type of qualifier to earn wages in a specific field. One such example is that most states require athletic trainers to pass a test and pay fees to a licensing agency before being able to work as an athletic trainer.

Occupational Licensing is a form of government regulation that requires individuals to pass some type of qualifier to earn wages in a specific field. One such example is that most states require athletic trainers to pass a test and pay fees to a licensing agency before being able to work as an athletic trainer.

However, this method causes:

I originally gave this as a presentation to a political-policy discussion audience. But I decided to make the full research-review available here.

So if you’re interested, enjoy.

Occupational licensing is a rapidly growing subject of debate in regard to labor market optimization. Many different labor market institutions have taken over the field of licenses, certificates, or registration to ensure a gatekeeper standard among all individuals participating within a specific field of employment.

These organizations typically claim what labor unions used to promise—Which is better labor market outcomes for those that participate in their process, (Gittleman and Kleiner, 2013) and better qualified licensees.

In an “ideal scenario” example, an individual would get licensed from a certifying agency, then proceed to receive superior support and better earnings potential since they are licensed. However, the government involvement in licensing as well as the barrier to entry control that the certifying agencies have on the supply of labor presents unintended consequences against this “perfect scenario”.

In this analysis, we intend to investigate the economic agents involved in licensing, their relation to the more heavily studied field of effects on wages from unionization, and determine how the overall labor market is affected by increases in national licensing requirements.

First, we will view the overall goals that licensing agencies are trying to achieve, the government’s objectives regarding allowing these agencies to operate, and the general objectives of non-licensed versus licensed labor market suppliers.

Then we will begin to consider the positive and negative aspects that occupational licensing brings to the labor market.

Next, we will bring all of this information together to present a connection between how labor market unions are correlated to occupational licensing.

Finally, we will investigate the areas that need more research and provide conclusions to the overall effect that occupational licensing has on the labor market.

From a free-market economist perspective, the best labor market objective would be full production where supply and demand are at an equilibrium. However, we need to look at the other economic agents involved and see their motives to truly discern objectives of each.

There are three types of occupational regulations: registration, certificates, and licensing. Registration is the least restrictive, and typically only requires filling out a form to send to the government. Certificates require successfully passing an examination by an accredited board. Licensing is the most extensive. To become licensed, you must successfully pass government standards and additional standards set by the accreditation agency.

First, we need to review licensing agencies. The licensing agencies are special-interest groups very similar to unions, in that their primary function is to seek what is best for their members (Card, 1996).

The next economic actor would be the skilled and unskilled laborers affected by the licensing protocols. Certainly, we can assume that highly skilled individuals that are able to get a license would be interested in doing so, and potentially then interested in ensuring that others cannot acquire one to drive up his or her own wages.

On the other side, low-skilled or medium-skilled individuals that may have a tough time getting a license in an occupation that requires it, could deem this as unfair treatment because they are actively trying to keep them out of the labor market.

To truly reconcile these differences between the economic agents, we look to the government. The government’s interest is in regulating labor supply quality through licensing.

The government’s prime concern is typically attempting to be the “middle-man”, or trying to leverage the principles of special interest groups (Such as licensing agencies) with the interests of the general public as a whole (Bryson and Kleiner, 2010).

The government accomplishes this by assigning agencies to review and distribute licenses to the qualified applicants.

The question then arises: How is the labor market affected in terms of quantity and quality of labor suppliers by allowing these type of licensing institutions to operate freely in the labor market?

Occupational licensing greatly benefits the individuals who hold a license. We view higher wages, lower unemployment, and greater likelihood of retirement/pension plans among those licensed by a certifying agency (Gittleman and Kleiner, 2014).

According to Gittleman and Kleiner (2014), the number of occupations that require a license from a federal or state institution has increased significantly in the past couple of decades.

This dataset by the two authors also indicates that the percentage of licensed individuals has also been increasing. The implication is that more individuals are being required to acquire a license to stay in the same occupation, or that new graduates must apply to a license before being allowed to originally operate within a career field.

Since more people are being licensed, more individuals share the aforementioned benefits of holding a license.

Increased knowledge and becoming “distinguished” are important parts of occupational licensing.

Consider going to a doctor that was not certified or licensed. Taking medical advice, or even discussing a problem with this unlicensed doctor, would make almost anyone suspicious about his credentials and expertise.

However, individuals go to doctors in hospitals often without even considering if the doctor could be wrong or misinformed. Why do we do this? The answer is simple; We intuitively know that the doctor is licensed or they would not be working at a hospital, and thus that license “distinguishes” him or her from an unlicensed practitioner.

Individuals know that the American Medical Association (AMA) has stringent requirements to be a member, and that ensures consumers to be at ease knowing the doctor has at least passed these basic guidelines.

Regulatory agencies can also force practitioners to keep up with modern-day technology by using the threat of license revocation (Bryson and Kleiner, 2010).

This can provide an easy way to hold labor suppliers to a very high standard, which can ensure adequate quality control. The regulatory boards also provide an easy way for anyone harmed to “obtain redress against malpractice, incorrect information or incompetence” (Bryson and Kleiner, 2010).

The biggest drawback to occupational licensing is in labor supply restriction. For our example, we will view the American Dental Association (ADA).

Suppose that we have a shortage of dentists in our country. In a free-market situation, we would expect the market to correct itself overtime to allocate enough dentists to provide their services in accordance with aggregate demand.

However, with occupational licensing the certifying agency can “block” a certain number of these applicants from acquiring a license, thus providing a ceiling on the labor supply (Gittleman and Kleiner, 2013 and Bryson and Kleiner 2010).

The ADA will do this because a shortage of dentists will typically raise the wages of currently licensed dentists, thus helping their own special interest group.

This limitation of entrants (dentists) harms the general population, because there is a shortage of dentists, which means longer wait times, overworked dentists, and higher prices/insurance costs.

Another disadvantage to the labor market that is caused by occupational licensing is the “closed shop effect”. Under this, regulatory agencies effectively monopolize their industry by prohibiting competition (Bryson and Kleiner 2010).

Since no one can join the field without a license, everyone must go through the same agency to acquire a license. This provides a monopoly effect for the licensing institution.

Since these institutions control the licensing requirements, they can even encroach on other, similar fields. It provides incentive for the regulatory agency to try to extend the scope of tasks of the occupation (Bryson and Kleiner 2010).

Many of the licensing agencies and their regulations vary across state lines. To examine this, we will look at personal trainers. Personal trainer requirements have significant differences depending on what state you reside it.

Consider a personal trainer in New York, for example. The personal trainer from New York almost certainly has to be certified, but also has to have a four-year degree (Bureau of Labor, 2016).

Compare this trainer to the personal trainer from California, who does not need a degree or even be certified (Bureau of Labor, 2016).

California and New York both have similar employment per thousand jobs (1.79 and 1.69, respectively) and both states have nearly identical location quotients (1.01 and .95, respectively) (Bureau of Labor, 2016). However, the annual wages of a personal trainer in California is $49,280, whereas in New York it is $54,050 (Bureau of Labor, 2016).

This provides very clear analytical findings that agree with Gittleman and Kleiner (2014) in considering that licensing/certification drives wages up in specific markets, while harming other less-restrictive markets. This makes the service more expensive, as well.

As mentioned earlier, if licensing agencies restrict entrant employment, it drives up wages and drops access to care. The question “how exactly do they restrict practitioners?” then arises.

A study by Bryson and Kleiner (2010) found that when the American Bar Association (ABA) sets the case questions for the license exam, they can simply raise the difficulty. When the ABA raises the difficulty of the examination by one point on the exam difficulty scale, entry wages increase by $1000. (Bryson and Kleiner, 2010).

In easier to work with terms, an increase in difficulty of 1% then increases wages by 1.7%. Since difficulty goes up, we can assume that the passing rate goes down because of the increased difficulty.

This explains the increase of wages since fewer people can pass, effectively reducing the number of labor suppliers in the market. One would assume that an increased difficulty would mean that the quality of the lawyers would then be better, because of increased standards.

However, the same study by Bryson and Kleiner (2010) found zero evidence of any quality effect. This essentially is how licensing boards can “restrict practitioners” and stifle the labor supply.

An interesting aspect of these studies is the connection between unions and occupational licensing. There are a few key points that draw unions and licensing agencies together, and a few things which dramatically separate them in terms of functioning.

The first item of interest is wages.

Unions and occupational licensing typically drive up the wages of the individuals who are involved with the union or are licensed (Lemieux, 1998).

However, unions do not raise wages evenly.

Unions increase the wage on average, but typically the workers with high skillsets on the far end of the distribution lose income compared to non-union work.

This results in highly skilled employees actually having a “comparative advantage” outside of the union sector (Lemieux, 1998).

An implication here is that occupational licensing would be a much better system for highly skilled workers, and would also increase quality because those with high skillsets typically would not want to be unionized if they are going to be receiving negative economic returns.

A big point of contention in modern day politics is wage inequality.

As noted above, unions compress wage differences through all skillsets, effectively reducing wage inequality (Card, 1996 and Lemieux, 1998).

Occupational licensing does not stifle any wages, or negotiate/barter the way that unions do. This results in licensed individuals not seeing a difference in their own distribution of wages compared to union workers (Bryson and Kleiner 2010).

The “union effect” of dis-incentivizing high skillset individuals does not seem to apply to occupational licensing.

Unions do have certain benefits over occupational licensing. Unions have the same monopoly effect over labor supply that licensing agencies do, but unions also have a voice effect that licensing agencies do not.

The “voice effect” means that unions can provide more than just a restriction on labor supply—they can also strike, have grievance standards, and also invoke seniority demands that licensing agencies cannot (Gittleman and Kleiner, 2013).

The study by Gittleman and Kleiner (2013) also showed that unions provide a greater economic return over licensing agencies and estimates that “macro-effect of unionization on wages” range from 15 to 20% on average.

Putting all of this together, we can see that unions and occupational licensing both have benefits and pitfalls when compared to each other.

One of the most important points in this comparison is to see that while they have some strong differences, the key points: labor supply restriction, special-interest wage increase, and the monopoly effect are constant between unions and licensing agencies.

Much similar to unions, if licensing agencies begin to feel the wage is not high enough for their field, they can “strike” in their own way by increasing the difficulty of entering the field. Both of these examples will result in lost productivity, a shortage in the labor market, and unfair regulatory agencies having extra power over labor suppliers/demanders.

Occupational licensing has its advantages and disadvantages.

The ability for an individual to be distinguished under a specific and regulated standard allows consumers to see a baseline level of requirements for the profession. The net benefit for those that hold a license in a required profession presents a positive economic return to them. This positive benefit is in the form of increased wages, employment opportunities, and benefits packages.

For non-license holders looking to get into the field, it provides many new obstacles. Many potential applicants will become disenfranchised and leave the field entirely, or be unable to pass increasingly difficult entrance exams.

The effect of these actions on the labor market is a reduction in the supply of labor. There does not seem to be any noticeable effect on the labor demand in regard to occupational licensing.

This provides an overall effect of labor demand staying constant, with supply restricted or diminishing, provoking a shortage of professionals in licensed fields. This shortage provides a net loss in the productivity of the economy as a whole.

It also negatively affects everyone in the labor market that uses the licensed services. The negative effects in the labor market would include increases in price of services, less access to licensed professionals, and the subsequent additional loss of productivity because of these two issues.

Based on the most recent applicable studies, it is evident that licensing agencies operate as more restrictive unions, with fewer benefits, and return a net overall loss on labor market applications, besides themselves.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2016-17 Edition, Fitness Trainers and Instructors.

Bryson, A., & Kleiner, M. M. (2010). The Regulations of Occupations. British Journal Of

Industrial Relations, 48(4). 670-675.

Card, D. (1996). The Effect of Unions on the Structure of Wages: A Longitudinal Analysis.

Econometrica, 64(4). 957-979.

Gittleman, M., & Kleiner, M. M. (2013). Wage Effects of Unionization and Occupational

Licensing Coverage in the United States. ILR Review. 1-31.

Gittleman, M., Klee, M. A., & Kleiner, M. M. (2014). Analyzing the Labor Market Outcomes of

Occupational Licensing. NBER Working Paper Number. 2014-27.

Lemieux, T. (1998). Estimating the Effects of Unions on Wage Inequality in a Panel Data Model

with Comparative Advantage and Nonrandom Selection. Journal of Labor Economics, 16(2), 261-291.

Read more about economics.

Comments are closed.

(Learn More About The Dominion Newsletter Here)

I think they are just as stupid as licensing. They don’t really “prove” you know how to do anything, its just a money-generating idea

Great for the certification agency, though.