Most Recent News

Popular News

Review of some recent (and not so recent) economic literature on various gender gaps.

When most people think of “gender gaps,” the first thing that comes to mind is the feminist wage-gap theory. But there are a few other “gap” areas that are just as interesting (albeit debatable).

When most people think of “gender gaps,” the first thing that comes to mind is the feminist wage-gap theory. But there are a few other “gap” areas that are just as interesting (albeit debatable).

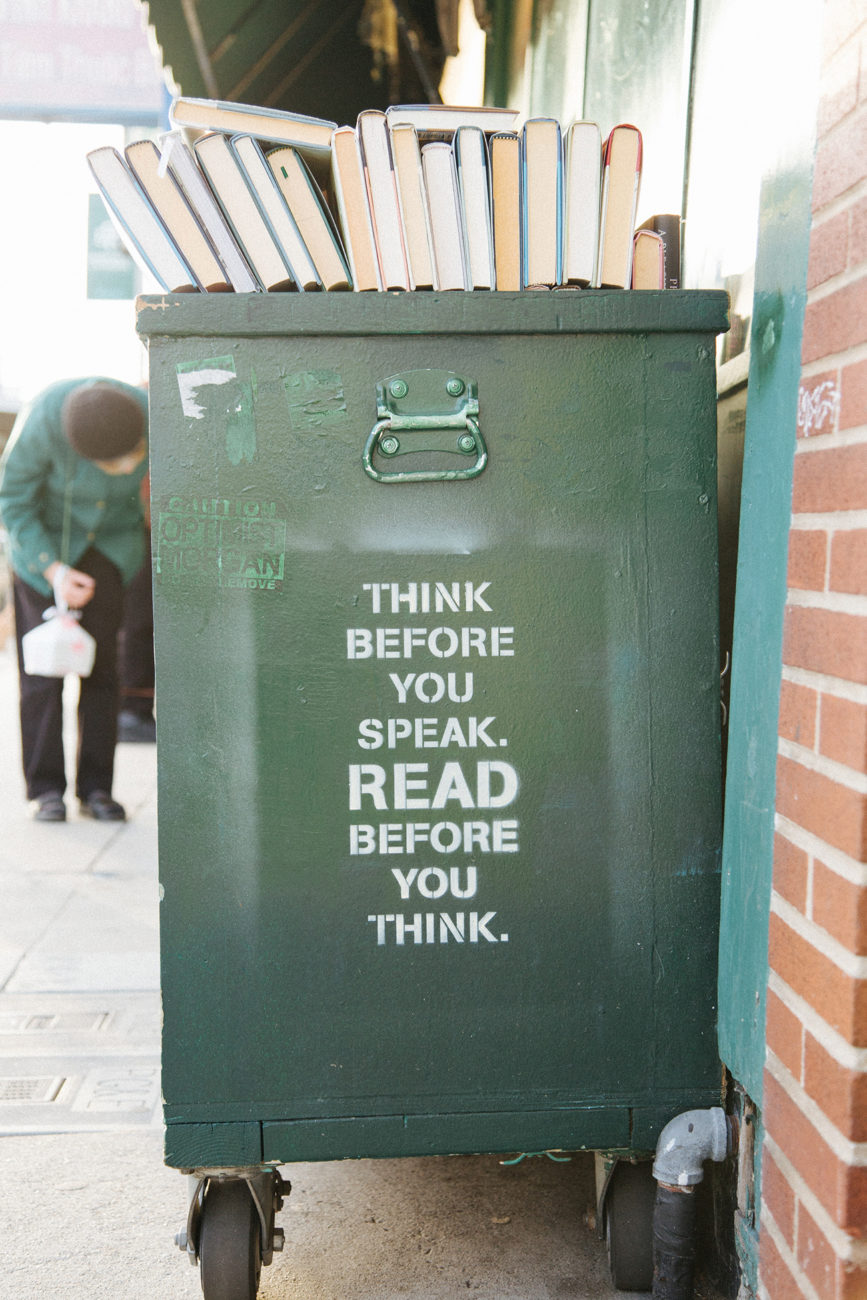

I stumbled upon a few journals and figured I’d post the abstracts here for anyone curious.

The careers of MBAs from a top US business school are studied to understand how career dynamics differ by gender. Although male and female MBAs have nearly identical earnings at the outset of their careers, their earnings soon diverge, with the male earnings advantage reaching almost 60 log points a decade after MBA completion.

Three proximate factors account for the large and rising gender gap in earnings: differences in training prior to MBA graduation, differences in career interruptions, and differences in weekly hours. The greater career discontinuity and shorter work hours for female MBAs are largely associated with motherhood.

We show that differences in childhood environments shape gender gaps in adulthood by documenting three facts using population tax records for children born in the 1980s. First, gender gaps in employment rates, earnings, and college attendance vary substantially across the parental income distribution.

Notably, the traditional gender gap in employment rates is reversed for children growing up in poor families: boys in families in the bottom quintile of the income distribution are less likely to work than girls. Second, these gender gaps vary substantially across counties and commuting zones in which children grow up. The degree of variation in outcomes across places is largest for boys growing up in poor, single-parent families. Third, the spatial variation in gender gaps is highly correlated with proxies for neighborhood disadvantage.

Low-income boys who grow up in high-poverty, high-minority areas work significantly less than girls. These areas also have higher rates of crime, suggesting that boys growing up in concentrated poverty substitute from formal employment to crime. Together, these findings demonstrate that gender gaps in adulthood have roots in childhood, perhaps because childhood disadvantage is especially harmful for boys.

This paper investigates the effect of gender-related culture on the math gender gap by analysing math test scores of second-generation immigrants, who are all exposed to a common set of host country laws and institutions.

We find that immigrant girls whose parents come from more gender-equal countries perform better (relative to similar boys) than immigrant girls whose parents come from less gender-equal countries, suggesting an important role of cultural beliefs on the role of women in society on the math gender gap. The transmission of cultural beliefs accounts for at least two thirds of the overall contribution of gender-related factors.

As the gender gap in pay between women and men has been narrowing, the ‘family gap’ in pay between mothers and nonmothers has been widening. One reason may be the institutional structure in the United States, which has emphasized equal pay and opportunity policies but not family policies, in contrast to other countries that have implemented both.

The authors now have evidence on the links between one such family policy and women’s pay. Recent research suggests that maternity leave coverage, by raising women’s retention after childbirth, also raises women’s levels of work experience, job tenure, and pay.

Recent evidence indicates that boys and girls are differently affected by the quantity and quality of family inputs received in childhood. We assess whether this is also true for schooling inputs.

Using matched Florida birth and school administrative records, we estimate the causal effect of school quality on the gender gap in educational outcomes by contrasting opposite-sex siblings who attend the same sets of schools–thereby purging family heterogeneity–and leveraging within-family variation in school quality arising from family moves.

Investigating middle school test scores, absences and suspensions, we find that boys benefit more than girls from cumulative exposure to higher quality schools.

Married women’s labor force participation (LFP) increased dramatically in the United States between the 1940 and 1960 cohort. The two cohorts lived under different divorce regimes (unilateral divorce rather than mutual consent).

The 1960 cohort also had a lower gender wage gap. We use a quantitative dynamic life-cycle model of endogenous marital status, calibrated to key statistics for the 1940 cohort, to study the effects of these two changes.

We find that both drivers combined are able to account for over 50 percent of the increase in married women’s LFP and also generate large movements in marriage and divorce rates.

I don’t necessarily agree with any of these journal articles. Just found them interesting. Enjoy.

For more economics, view the economics sub-category.

(Learn More About The Dominion Newsletter Here)